So, today we had part two of the critique for our Liquid Words assignment. We spend a long time on each piece, which is good, since it is not so much about the pieces themselves we are talking about, but rather how to look at pieces in general, and how to interpret 'art' as a whole. At least, that is how I look at it. I think it is very important and useful to do it this way because of a couple of things. First of all, we are in a class room setting, wich means we are a group of people, each student possibly having a unique interpretation of each piece. To me, the most important part is actually to listen to all the initial (in particular) reactions to my own piece, since I will have a preconcieved notion or intent with what I am attempting to communicate. When those notions comes out as false, or if they would happen to be right, I learn a lot from that. This does not say that what I have made is good art or bad art, it simply tells me something about my own abillity to communicate my own ideas. Those ideas can be good, unique, deep, or they can be vulgar, shallow, superficial. There is little point in having brilliant ideas or concepts in your head, if you're unable to let them come through in your art. My point is, this is a unique opportunity we have as artists to listen so closely to what a whole group of devoted peers have to say about our own art. After school, you just might have to totally trust yourself, looking back at the 'classroom days' and whish you had a group of people telling you what they feel about your art again. It is pretty useful.

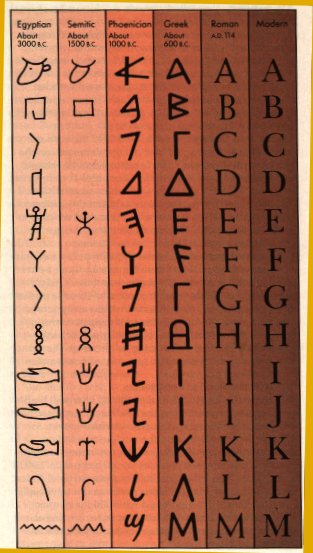

Another thing that comes to mind from todays critique was the question "What's wrong with english?", in other words, why didn't I just use english if I tried to communicate something through words? (I guess this might be obvious to some people, but I say it anyway) First of all, english is not my native language, so what is wrong with norwegian? Second of all, by using something other than english, I was actually communicating 'something' other than just what the meaning of each word 'means'. Third, Grendel–which was based on the epic poem Beowolf–was written in a language that was totally understandable for scandinavians of that time (700 - 1000 AD), and even today I can look at that text and more or less understand it based on my knowledge of norwegian, not english. So, what once was old english, has much more in common with scandinavian today than with english. This is for me a 'proof' that words and language is actually very liquid, they are in a constant flux, either you like it or not. True, some languages do not change as much as others, but they still change.